I joined the Royal Navy at sixteen with a simple, unshakable belief: if you work harder than the person next to you, the system will reward you. I spent the next thirty years testing that theory, only to discover that the goalposts of life are often made of sand.

By the age of twenty-eight, I was a Chief Petty Officer with a dream of teaching. I spent five years grinding out an Open University degree by the dim light of a cabin lamp while the ship rolled beneath me in the Persian Gulf. I did the work. I secured a placement to start teacher training—provided I passed the Admiralty Interview Board for a commission. But the moment I reached the door, the Navy slammed it: Recruitment freeze led by the phrase "I'm sorry we are not recruiting education officers any more". Sociologist Max Weber once described the "Iron Cage" of bureaucracy—a place where rules become so rigid they lose sight of the humans within them.

The Signal and the Noise

I pivoted back to Engineering, my core skill set. I rerouted and passed the Special Duties (SD) Officer exams first time and sat on the Officer's " selection roster"; yearly watching as my peers and the friends I had joined up with back in the day, selected and wearing a different uniform, while I had been off on the "Education route." One afternoon, my boss came to my house to tell me I’d finally made Officer. Me and my then first wife celebrated in my living room cracking open a bottle of Champagne. But the joy was short-lived. He had misread the signal. I had passed, but I wasn't "selected." I was merely a name on a list that wasn’t moving.

The Ghost of the Yangtze

By the year 1994, I had reached the rank of Charge Chief Petty Officer aka a Senior Maintenance Rating or "SMR"—almost at the pinnacle of the "Lower Deck." I was leading a small ships flight of two Sea King helicopters. In the latter part of 1997, we were at the edge of the world, primed for a mission to rescue expats from the encroaching chaos of the civil war in the Congo. The air was thick with the name of Johnny Paul Koroma and the threat of the African interior.

[In second quarter of 1997, Major Johnny Paul Koroma led a bloody military coup in Sierra Leone, overthrowing the democratically elected government. He formed the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) and, in a move that horrified the international community, invited the Revolutionary United Front (RUF)—a rebel group notorious for mass amputations and using child soldiers—to join his junta.]

For days, we waited at Pointe-Noire in the Ivory Coast, for the fuel we needed to transit the Congo River. We stripped our Sea Kings of their anti-submarine gear, converting them into passenger-carrying lifeboats. I was issued Kevlar body armour, spent my mornings at shooting practice off the back of the ship, and choked down malaria medicine. The signals coming down the line were headed with a chilling warning: “Remember the Amethyst.” It referred to the 1949 Yangtze Incident where a British ship was trapped and fired upon by Chinese forces. We were living that history. I even sat in my cabin and wrote a goodbye letter to my wife, just in case.

Then, the government shifted, because we were refused fuel and the Royal Marines were sent in, and we stood down. We reconverted the aircraft to their original role, and the ship sailed for Cape Town to celebrate Nelson Mandela’s jubilee. I traded my Kevlar for a ceremonial uniform and marched through the city of Cape Town with my whole ship’s company, led by a field gun from the Siege of Ladysmith. It was a tribute to the Naval Brigade of 1899, who had saved a besieged city by hauling heavy ship’s guns over land across the African veldt. I was walking in the shadows of giants.

[In April 1997, HMS Chatham visited Cape Town as part of the celebrations for the 75th Anniversary of the South African Navy. The "Freedom of the City" parade featuring the ship's company in their tropical whites and the field gun crew, was a major highlight. It served as a symbolic "return" of the Royal Navy to South Africa in the post-Apartheid era, specifically honouring the historical ties of the Naval Brigade]

The Make-Believe Board

Fast forward to the year 2000, I had made it to Warrant Officer, the top of the Royal Navy's lower deck. It was in this state of high-stakes reality that I was coaxed by the Commander of my air station to give the Admiralty Interview Board, the AIB which selected potential ratings and new civilian applicants for the Upper Deck, Officer Status - I thought okay, one last go. My exams were still valid; my record was impeccable and the age limit had been dropped, once again, I dreamt of success in achieving the top of my personal goals - "My tree".

For three exhausting days, I was judged on make-believe scenarios and my choice of literature, I didn't impress them with my poor mental maths . They chose "potential" over "proven," selecting younger and those civilians straight out of Uni the candidates who looked the part they had scripted. They dismissed decades of operational service—including the man who had just prepared to fly into the Congo—with a pompous finality: “You are probably a very good Warrant Officer, but we won’t be taking you on today.”

On the drive back to base, the weight of twenty years of "almost" finally crushed me. I pulled over on the hard shoulder and cried. I wasn't just crying for a rank; I was grieving for the meritocracy I thought I lived in.

The Bridge to the Grass

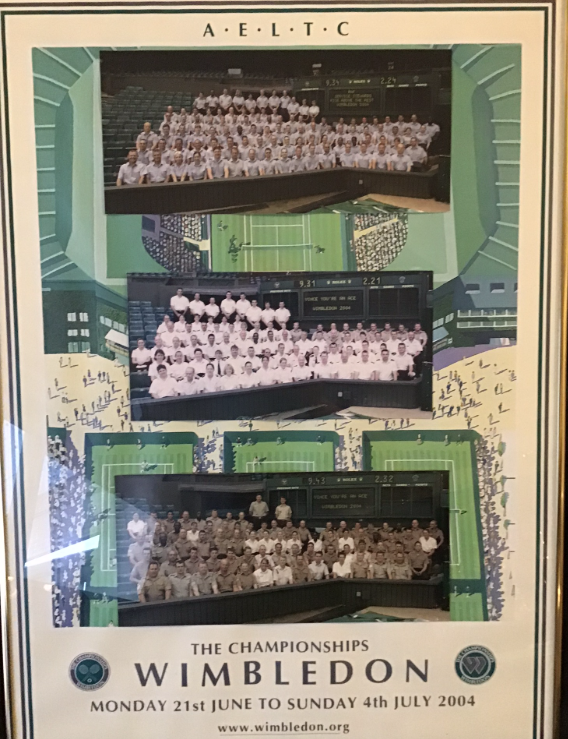

If I had stopped there, the story would be a tragedy. But a "Crisis Point" is just a turn in the road. Because I stayed the course, a different door opened. I was selected to lead the tri-service team at Wimbledon. For seven years, I managed 300 personnel at the world's most prestigious sporting event. The Navy didn't give me the commission, but they gave me a stage most Officers would have given anything to stand on. In 2005, I left the service early at 47, I was working as a member of the Department of a Trade and Industry’s 'export control licence team'; and in my spare time continued as the executive Warrant Officer for the 2nd Sea Lord, recruiting and managing those 300 Tri-Service stewards for the All England Lawn Tennis Championships held every late June and early July But it was now time for a new adventure - Civvy Street!

The Single Point of Failure

Since transitioning into a 'Strawberry Mivvie'—or what the officers would politely call 'plain clothes'—I have navigated a civilian world filled with 'Red Flags.' I call them the Silas Snakes and the Barnaby Bullies: the Machiavellian architects who view your talent not as an asset to be nurtured, but as a ladder to be climbed and then kicked away.

One such manager harvested my expertise to secure a massive contract deal. I had worked over three years on that project and was on a trajectory to run my own department—but it wasn't to be. The firm brought in a Silas Snake. From the moment he joined and took over my team, he kept me wrapped in the 'Velvet Glove' of corporate flattery and perceived necessity. He played the perfect courtier, smiling as I mentored the team, even as he was quietly poisoning the well. He turned those I had mentored over seven years, and even my own Best Man from my second wedding, into instruments of my exclusion. The moment the ink was dry on the contract, the glove came off. I was escorted from the building like a trespasser in a house I had built, crying in my car while my youngest stepdaughter watched.

The architecture of these people is designed to be elusive. Even now, looking for the companies they run is like chasing ghosts in the fog. Names will guide you to 'beware of the beast'—brands replaced by a legal shadow like 'Ferox' (meaning Fierce) or buried in legalese under a series of dissolved entities and compulsory strike-offs claiming to be noble. You may have entered a world of smoke and mirrors where the brand is the 'Velvet' and the shifting legal paperwork is the not-so-Noble 'Iron.'

The cycle of the 'Iron Fist' doesn't stop with my generation. Just last October, my eldest grandson secured what he thought was his dream job. He entered with the same innocence I once had, only to quickly identify the rot beneath the floorboards. He discovered flagrant breaches of Health and Safety and a casual disregard for GDPR—his boss even sent videos of him falling over he had captured on CCTV and sent it round his employees as a 'joke.' He did the right thing; he spoke up. Two weeks later, the 'Velvet' was stripped away. He wasn't given a handshake or a meeting; he was fired over the phone by a Barnaby Bully.

It seems the modern corporate playbook is simple: if you see the failings, if you hold the expertise, or if you possess the integrity they lack—you are a threat to be neutralised.

What I’m Trying to Say

I see these "Crisis Points" appearing now in the lives of those I love. My eldest stepdaughter is facing the "not yet" of her law exams. My grandson was fired for standing up for his dignity. My youngest daughter is facing a "no-fault" eviction.

To all of them, I say: The system is not the truth.

Decisions made at these "Critical Junctures" are the only ones that matter. The Navy board, the toxic manager, the London rental market—they are all gatekeepers. But if one gate is locked, you don't stop being a traveller.

I am now at retirement age, recovering from prostate cancer. I want my grandchildren to see that I am not defined by the commission I never got or the job I was forced to leave. I am defined by the fact that I kept moving.

Ruthlessness is just the wind trying to blow you off course. They can take your job, your rank, or your flat—but they can never take the fact that when the crisis came, you didn't break.

You just found a better map!

Poem

Don’t give up on yourself my friend,

Push in, rise up, there is a means to the end.

Don’t fear the bullies, the Baron, or the sea,

Take in those crises points, and think of me.

Believe in yourself, be the one to gain,

Crises will come and go, you are not to blame.

Rise above the rest, is the best way to go,

“Remember the Amethyst,” and courage will grow.

Author’s Note: In the Royal Navy, we are taught to "adjust our sails" when the wind changes. My career didn't follow the charts I drew at sixteen, and the corporate world often felt like sailing through fog. But looking back from the shore of retirement, I’ve realised the rank was just the ship—the integrity was the hull. To my loved ones, my sons, step children and my grandchildren and of course to my readers : the goalposts will move, but as long as you keep moving, you are never lost.