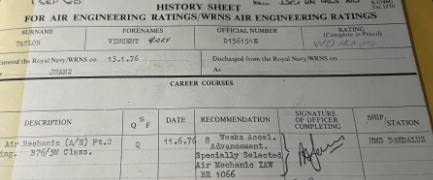

The biting Cornish wind whipped across the airfield, carrying the tang of salt and the roar of a 771 NAS Wessex helicopter struggling against the gust. It was May 1976. For a 17-year-old Junior Naval Air Mechanic like myself, fresh from training at HMS Daedalus, it was a long-awaited arrival. I'd been held back there to retake my Naval Maths and English Tests, having left HMS Ganges with a rather dismal 6 in Maths and a 3 in English – a NAMET 6-3, as it was termed. Ironically, I'd won the top tech award in parts two and three training (over fourteen weeks), earning the coveted "Specially Selected Air Mechanic" title, or "Super Sam" as everyone called it. This gave a youngster like me fourteen weeks of accelerated advancement to Leading Hand, or 'killick'.

So, finally, I was drafted to HMS Seahawk, the Royal Naval Air Station Culdrose, in Helston, Cornwall. The train journey from Portsmouth, kit bag in tow, ended at Redruth railway station. There, a Petty Officer and a bus driver met us, loading us and our gear into the naval blue vehicle for the 28-minute trip from Redruth, through "Foggy Four Lanes" past Poldark Mine, the Seal Sanctuary and the then Cornwall Aero Park in Helston, and finally to Culdrose Main Gate.

Stepping off the bus, kit bag slung over my shoulder, I was immediately immersed in the sights and sounds of a busy naval air station. Sea Kings, their distinctive "wokka-wokka" sound filling the air, were everywhere. Ground crew scurried about, preparing the machines for flight. The smell of aviation fuel hung heavy, a constant reminder of the powerful machines I was now a part of.

1976 was a year of extremes. The cinemas showcased "All the President's Men" and the nascent "Rocky" phenomenon. Disco dominated the music charts, with ABBA's "Dancing Queen" and the Bee Gees' "You Should Be Dancing" ruling the airwaves. Punk rock was a distant rumble. For a 17-year-old more interested in fixing helicopters than following fashion, it was all background noise. More importantly, 1976 was a scorcher – the hottest summer on record in the UK. Drought, water shortages, and standpipes were the real headlines. We didn't even think of a term for it other than "Fucking hot." Nowadays, we turn to one another and say "Global Warming?"

Culdrose, nestled in the Cornish countryside, wasn't far from some stunning beaches. Gunwalloe was the closest, with Mullion Cove not far beyond. These sandy stretches were popular with sailors and WRNS alike, those waif-like individuals who offered a welcome break "off watch" for catching some rays, enjoying a few beers, or even having a "banyan" on the beach. Being seventeen among these spirited women was a thrilling experience. Their confident laughter, playful banter, and mischievous glances often turned ordinary moments into unforgettable adventures. The WRNS brought a lively energy to Culdrose, transforming the beaches into vibrant scenes of youthful exuberance and camaraderie.

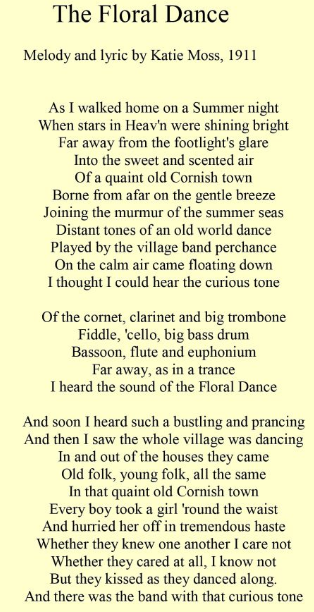

This was to be my home from 1976. I soon discovered the following year, that on May 8th annually, it played host to “The Helston Furry Dance,” also known as the Flora Dance. This traditional Cornish folk dance, dating back to 1790, saw the town come alive. Local schoolchildren of all ages danced through the streets, followed at midday by the adults. Ladies and gentlemen, partnered up, followed the local band in procession, performing seemingly simple but specific steps.

The dancers moved in groups of four, two couples side-by-side (ladies on the right), through the streets and sometimes even buildings. The dance consisted of a "step, step, step, hop" sequence repeated three times, followed by the same sequence repeated twice. Partners then changed places, gentlemen passing right shoulders and briefly turning to face the opposite lady before returning to their original partner, and the "step, step, step, hop" sequence began again.

The "Furry Dance" is thought to derive from the Cornish word "fer," meaning "fair" or "feast." Some theories suggest it originated as a pagan ritual celebrating the earth's fertility and the return of spring.

The air in Helston during the festival hung thick with the scent of lilies and anticipation. As the dancers, bedecked in their finery, began their procession, a peculiar feeling settled over me. It was a blend of the familiar and the utterly strange. The rhythmic "step, step, step, hop" echoed through the streets, a hypnotic pulse. I couldn't shake the image of the Wicker Man, though this celebration seemed far removed from such overt sacrifice. Yet, there was a primal energy in the dance, a connection to the land and the changing seasons. The Hal an Tow, a riotous explosion of noise and blackened faces, added another layer of mystique, embodying the wilder spirit of the festival.

The girls, with their floral garlands, moved with a grace that belied the relentless rhythm. They seemed almost otherworldly, like the ethereal figures in "Picnic at Hanging Rock," caught between the present and some long-lost past. Their smiles held a hint of something unknowable. It was a reminder that even in the modern world, echoes of pagan rituals, the chaotic energy of the Hal an Tow, and the power of tradition can still exert a powerful hold.

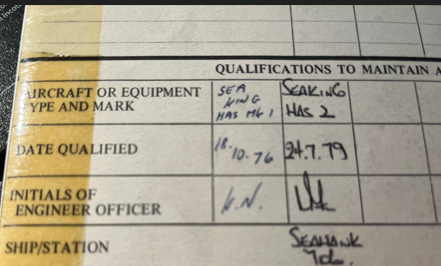

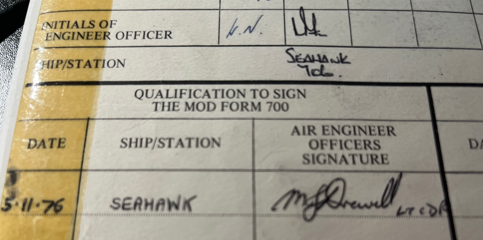

I, though, had made it through Ganges, Daedalus, and now Seahawk, joining 706 NAS, the Sea King Helicopter Anti-Submarine Mark 1 squadron. My heart hammered as we newbies, berets on, marched in single file over the bridge to "D site" for our induction. The hangars housed nine ten-ton Sea Kings and over 100 personnel, operating in daily watch routines.

I was in "Janner land" at HMS Seahawk, or RNAS Culdrose. As I was under 18, I was issued a station card, requiring me to sign in and out whenever I left base. The town was an easy walk from the main gate, a tempting destination after a few beers. Gunwalloe was also within walking distance, with the Halzephron Inn a welcome stop before the beach.

[Jackspeak: Jan/Janner Nickname for any sailor from the West Country and by extension, anything that originates from Devon or Cornwall, strictly speaking a Janner is a Devonian - a Cornishman is a Jagger but the two terms have become interchangeable in modern naval usage.]

My 'mess' (home in Jackspeak), was allocated with four five sailors and mine was with Geordie lad, a bit older than me, who we named, funny enough, George (but he answered to his shortened surname Jamie). I got to know him as Ian and in those days he had the "motor", which was a Triumph 2500TC. He insisted the "TC" stood for "Twin Carburettor," promising improved performance. However, we soon learned it was more of a "towed car," prone to unreliability.

Jamie, who became a good friend, was further ahead in his qualifications (QM and QS). He called his car "Bonnie lad" and would mimic winding it up like a toy car when it struggled.

Joining 706 Squadron was a whirlwind. The Sea King was far more complex than training aids. Senior mechanics, like Jess Willard, Taff Ashman, and later my Chiefs, Gurney Fern and Sandy Sandford, seemed like grizzled veterans.

At seventeen, I was assigned to a team, learning the intricacies of the Sea King's airframe, engines, hydraulics, rotor blades, and gearboxes, all regularly checked by "Flex ops" like us. The pressure was immense.

Although the demanding schedule of part four training, learning to maintain the aircraft, and taking the exams required for signing them off took a while from May until November of that year, it never though our limited beach visits, or sunshine sessions at Gunwalloe or those rides in Jamie's TC; they were a much-needed luxuries for us matelots of the Fleet Air Arm.

Oh, but, the camaraderie was pure gold! The banter, with memorable characters like Ian (Jan) James, Stevie Jeffs, and Marty Southard, not to mention "Oor Jamie" Jamieson, kept things lively. And who could forget the "farting females" – Joyce (Saunders), Randy Mandy, and the hypochondriacs Helen and Anne? The laughter was relentless. But beneath the jokes and jabs, there was an unspoken bond. We were a team, playing our part in the vital mission of the Fleet Air Arm. The Sea King wasn't just a helicopter – it was a hero, saving lives at sea and being the rock-solid cornerstone of Search and Rescue in the South West. Every mission fuelled our pride and sense of purpose.

At 17, the world felt vast and uncertain. Leaving home, joining the Navy, and the intense world of 706 Squadron was daunting. But as I stood on the D site hardstanding, sometimes at night with marshalling wands in hand, the roar of a Sea King's engines vibrating through my boots, I knew I was where I belonged. The future was unwritten, but for now, I was part of the Fleet Air Arm, and that was enough.

POEM Choice

Short Poem From VGT

Seventeen Summers in '76: Memories of Rum, Romance, and the Furry Dance.

Initiated at seventeen, back in '76, those scorching days (and sultry nights),

We were all so young, so green, ogling the WRNS, jahooblies and their sexy black tights!

With Rum, Beer, and Beaches, and the occasional (odd) romance,

it was just me and my mates, fresh sailors, first to be matelots,

In the Angel every May, we’d catch the “Furry Dance,”

And in those brilliant days, we would end singing, “all together in the boating lake.”