Isn’t it curious how much we Brits seem to admire the Dutch? It’s almost a national quirk—a tendency to find something un-British in the things we do, support, or quietly admire. Take Liverpool Football Club, for example. Some people adore them, not just for their history but for their strong Dutch connections: a Dutch manager, a Dutch fullback, a Dutch midfielder, and even a lethal Dutch striker. It’s practically the Netherlands’ unofficial XI, thank heavens for Luke the Nuke Littler!

But let me be clear: I am not one of those people. In fact, I have no time for Liverpool FC at all. My connection to the Dutch stems from something far less glamorous but infinitely more memorable—three months spent with the Dutch navy during my own time serving in the Royal Navy, or “the Andrew” as we sailors like to call it.

And before you ask, the nickname “the Andrew” has its roots in naval tradition, supposedly a reference to a zealous 18th-century press-gang leader named Andrew Miller, who was so efficient at rounding up recruits that the navy was said to belong to him. It’s a fitting bit of folklore for an institution as steeped in history as ours.

Those three months with the Dutch navy, however, left me with a different perspective entirely—on camaraderie, discipline, and, naturally, the occasional cultural clash. Little did I know they’d also give me some of the best stories of my naval career, including one or two that might explain why, even now, I can’t help but raise an eyebrow at all things Dutch.

HNLMS Zuiderkruis (A832) was a replenishment oiler of the Royal Netherlands Navy, commissioned in 1975 and decommissioned on 10 February 2012. The ship was designed to provide underway replenishment to naval vessels, supplying fuel, ammunition, and provisions to both national and NATO units at sea.

The design of Zuiderkruis was based on the earlier replenishment ship HNLMS Poolster, featuring enhancements that enabled “one-stop replenishment.” This capability allowed the ship to supply various necessities, including aviation fuel (AVCAT), fresh water, and spare parts. Additionally, Zuiderkruis was equipped with a helicopter deck and hangar, facilitating vertical replenishment (VERTREP) operations using up to three helicopters. In the first part of the new year 1984, I was assigned to 814 squadron in which I was a crew Chief Petty Officer working with three embarked Sea King helicopters.

Throughout its service, Zuiderkruis participated in several notable operations, but my squadron embarked on a three-month jaunt which included Canada , the USA and a trip to the Netherlands Antilles which included Aruba and Curacao and was probably the most memorable of my career.

Serving aboard the Zuiderkruis was an adventure in many ways, but one of the biggest surprises for us British sailors was the food. We Jolly Jack Tars were accustomed to hearty English breakfasts—bacon, eggs, beans, and perhaps a few fried slices—and dinners that nearly always involved chips. On this Dutch vessel, however, we were thrown into a culinary world that was both foreign and, at times, baffling. Every time, we sat down to a meal, someone next to me would say Eet smakelijk pronounced ‘ate smarklick’ which we soon found out to mean ‘enjoy your meal’.

Breakfast, or ontbijt as the Dutch called it, was a stark departure from our familiar fry-ups. The spread typically included slices of bread (brood), which we naturally assumed were meant for toast—except there was no marmalade, no proper jam, and not even a toaster in sight. Instead, they offered butter topped with hagelslag, which, to our bewilderment, turned out to be chocolate sprinkles. Eating what looked like a dessert topping for breakfast felt almost rebellious, though I’ll admit, a few of us secretly developed a taste for it.

For those of us who preferred savoury options, there were slices of Gouda or Edam cheese, cold ham, and salami. These were paired with what we came to call “picnic eggs”—hard-boiled, and to our thinking, utterly misplaced on a breakfast table. After about four weeks of staring at the same cold meats and “picnic eggs,” frustration started to bubble up. We’d often rant at the chefs and stewards, “Do you even have a cooker?”

“Yah,” they’d reply with an infuriating shrug.

“Well,” we’d snap back, “do you know how to switch it on?”

One morning, one of my crew approached me at work with a look of utter disappointment. “Do you know what I had for breakfast this morning, Chief?” he asked, shaking his head.

“What?” I asked, bracing myself for the answer.

“A tomato,” he said flatly.

“Oh, that’s not so bad,” I replied, trying to be optimistic.

“In water,” he added, his voice tinged with despair.

I couldn’t help but laugh, but deep down, I knew we all shared the same longing for a plate of something warm and familiar. Even a soggy tomato couldn’t make up for a missing fry-up.

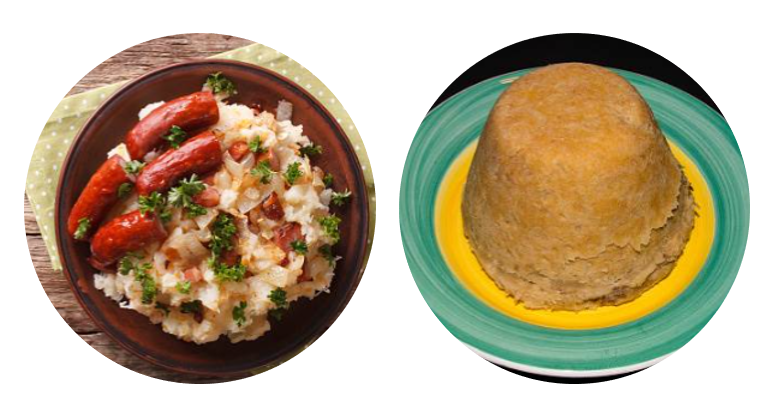

Dinner, or avondeten, was yet another test of our adaptability. The Dutch seemed to favour practical, hearty dishes like stamppot—a literal mash-up of potatoes and kale or other greens, served with a fat smoked sausage called rookworst. It wasn’t bad, really, but it lacked the comforting crunch of chips or the familiarity of bangers-and-mash or a good old steak and kidney pudding (fondly known by Jack as “baby’s head”).

We found ourselves longing for something fried, and once a week, we’d get lucky with a burger or a rissole. If we dared to ask for more—maybe trying our luck with, “Can I have my oppo’s portion since he’s not coming today?”—the steward would flash a grin and reply very matter-of-factly, “No, you’ve had your ration today.”

But the real challenge came with the fish dishes. Pickled herring or smoked mackerel often appeared on the menu, rolled up neatly and served cold. For me, that was a step too far. I couldn’t even look at them without my stomach doing somersaults. While some of the Dutch crew tucked in as though it was the finest delicacy, I stuck to the safer options—anything that didn’t resemble bait or smell like the docks.

As if the Dutch cuisine wasn’t disorienting enough, there was the unexpected prevalence of Indonesian food. Dishes like nasi goreng (fried rice), satay, and rendang were regular features on the menu. The Dutch love for Indonesian flavours made sense when you learned about their colonial history with the Dutch East Indies, but for us, it was strange to see fried rice served alongside a fish finger and a fried egg. The combination of sweet soy sauce (kecap manis), spices, and a runny yolk wasn’t something we were used to, but to the Dutch crew, it was as normal as pie and mash was to us.

One sailor, after his first encounter with nasi goreng, quipped that it tasted like the galley had accidentally mixed breakfast, lunch, and dinner into one chaotic dish. Another likened it to “posh egg fried rice,” which, to be fair, wasn’t entirely off the mark. Initially, we approached it with scepticism—eyes narrowed and forks hovering cautiously—but over time, some of us grew oddly fond of it. Of course, we couldn’t resist seasoning the experience with a heavy sprinkle of British irony.

It was a good thing, though, that one enterprising sailor had the foresight to smuggle aboard an entire case of Pot Noodles. When the nasi goreng didn’t quite hit the spot—or when someone drew the short straw and got the fishy leftovers—it was comforting to know a stash of instant noodles waited in the mess. The sight of a sailor clutching his steaming pot, muttering about “proper grub,” became a regular occurrence, proving that sometimes culinary survival depends on nothing more than boiling water and a foil sachet of powdered flavouring.

By the end of our stint aboard the Zuiderkruis, the food had become a running joke among the crew. We referred to the thin soups as “wishy-washy broth,” mocked the cold fish rolls as “bait,” and started smuggling sachets of ketchup from the shore based visits to McDonalds to liven up the blander meals. But secretly, many of us had learned to appreciate the variety and even looked forward to the occasional bowl of nasi goreng.

Food may not have been the highlight of our time with the Dutch navy, but it added a layer of cultural immersion that none of us could forget. And though we might have grumbled at the lack of chips, the experience broadened our horizons in a way only time at sea can.

Another fascinating titbit the British sailors learned aboard the HNLMS Zuiderkruis was its historical significance: in 1981, it became the first ship in the Dutch navy to welcome female sailors into its ranks. This progressive step was a point of pride for the Dutch crew but also came with a stern warning.

During the embarkation briefing, the Captain, in no uncertain terms, laid down the law: a strict “no touching” rule. Any sailor caught breaching this code of conduct would find themselves swiftly and unceremoniously drafted home—or worse, reassigned to a far less desirable post. The Captain’s address left no room for misinterpretation, but the reality of a confined ship at sea proved a challenge for certain members of the crew.

“Jack,” as British sailors colloquially refer to their more daring shipmates, decided to test the waters of this prohibition. By the time the ship reached Curaçao, the inevitable had happened—an outbreak of “crabs” among the lower deck crew. It was an unspoken scandal; no one admitted to being patient zero, but the infestation spread with remarkable efficiency. Whispers circulated the ship, jokes were shared in hushed tones, and all fingers pointed (figuratively, of course) at the mingling of Jack and the Dutch ladies.

The Captain, hearing of the outbreak but lacking a confession, enacted a ship wide effort to eradicate the problem. The most memorable sight was the Dutch women’s mattresses being hauled onto the upper deck, where they were subjected to an aggressive “overhauling.” Crewmates armed with beaters attacked the mattresses with fervour, clouds of dust—and presumably the unwanted pests—rising into the air. The spectacle was both comical and symbolic, a scene that would etch itself into the memories of those aboard.

While no further fraternisation was officially reported, the sailors’ jokes about “no-touching rules” and the “Curaçao crabs” persisted for the rest of the voyage, becoming an infamous chapter in the Zuiderkruis’ storied career.

Our three Sea Kings disembarked in Curaçao, and with the ship safely moored, we were granted some well-earned shore leave. Jack, being Jack, headed straight for the beach, while the rest of the lower deck—freshly free of their recent “crabs” debacle—gravitated toward the island’s infamous establishment: Camp Allegro.

The name had a ring of irony to it, as there was little musical about the place, but the lads had rechristened it with their usual subtlety, dubbing it “Camp A Leg Over.” And indeed, the camp bore more than a passing resemblance to the infamous “Chicken Ranch” from that Dolly Parton film. It was a sprawling compound just far enough from the town centre to provide discretion, yet close enough for easy access. A wrought-iron gate framed the entrance, the name “Camp Allegro” barely visible in faded paint, and the grounds were bordered by palm trees that cast wavering shadows in the warm Caribbean breeze.

We Senior Rates went along for an experience one day and to ensure our lads didn't get get up to anything problematic. Inside, the place was a mix of charm and chaos. The main building—a weathered, colonial-style villa with peeling whitewashed walls—housed the bar, which always seemed sticky underfoot. Dimly lit, the air was thick with cheap perfume, cigarette smoke, and laughter. The walls were adorned with mismatched pictures: posters of sultry women, a few faded nautical maps, and even a random dartboard that had clearly seen better days. In the back, private rooms were available for those willing to pay a little extra—a fact Jack and his mates were all too familiar with.

The allure of Camp Allegro was undeniable, and for some of the lads, it quickly became an obsession. One sailor, in particular, made it his second home, squandering what must have been a small fortune on its “amenities.” His visits became so frequent that when the ship prepared to depart, he didn’t even make it back aboard. He had overslept, still tangled in the haze of passion and Camp Allegro’s cheap sheets.

When the errant sailor finally faced the Captain’s table, the scene was equal parts drama and farce. The prosecutor laid into him, accusing him of gross dereliction of duty. But the sailor, not one to shrink under pressure, gave a spirited defence. He explained that he had done everything possible to wake up on time. His only mistake, he claimed, was underestimating the unpredictability of passion.

Apparently, during the “height of the moment,” he had tried to wind up the alarm clock on the bedside table to ensure he wouldn’t miss the ship’s orders. But in the chaos that followed—dim lighting, disrobed garments, and enthusiastic acrobatics—her knickers had somehow found their way around the clock’s clapper. As a result, it didn’t chime, leaving him to oversleep and ultimately hitch a humiliating ride back to the ship aboard one of our Sea Kings.

The Captain, though clearly unimpressed, struggled to keep a straight face as the explanation unfolded. The sailor received his punishment, but not before the story became legendary aboard the ship—a cautionary tale of love, alarm clocks, and the unpredictable pull of Camp A Leg Over.

By the time our stint aboard the Zuiderkruis was nearing its end, we thought we’d seen all the ship’s galley had to offer. After weeks of wishy-washy soups, cold fish rolls, and the endless parade of boiled eggs, we had all but resigned ourselves to the Dutch navy’s peculiar culinary habits. But then came the ship’s piece de resistance: a “dining in” night to mark the end of our time aboard.

We expected little more than a slightly polished version of the same fare—perhaps a slightly less watery soup or, if we were lucky, one of those rare rissoles. So, you can imagine our astonishment when the evening began with prawn cocktails, beautifully presented in proper glassware with a swirl of tangy Marie Rose sauce. For the main course, we were served none other than Steak Diane, expertly seared and flambéed in a rich, buttery sauce. The transformation of the ship’s galley was nothing short of miraculous.

The crowning moment, however, was dessert. The menu called it “Omelette Vesuvius,” which, based on past experiences, we assumed meant some kind of egg-based pudding. By now, most of us were egg-weary, to say the least. When the steward came to ask if I’d be having pudding, I waved it off and said, “Oh no, I don’t want another bloody egg.”

But then the moment arrived. As the desserts were brought out, gasps spread across the room. It wasn’t a boring egg custard or some bizarre soufflé—it was Baked Alaska! Perfectly browned meringue atop layers of sponge and ice cream, still frozen despite the flambé. The presentation was a spectacle in itself, and those who’d opted in were suddenly the envy of the room.

I couldn’t help myself. “Oh my!” I gasped, my earlier regret washing over me. “Can I change my mind?” I called out to the steward, practically pleading.

He gave me a smile that was equal parts smug and sympathetic and replied, “Sorry, sir. You already had your ration. No second helpings tonight.”

The rest of the table burst into laughter, but I sat there watching the lucky ones savour their Baked Alaska with an expression of pure culinary heartbreak. I’d never live that decision down.

It was only later that we discovered the truth: the ship’s cooks weren’t the amateurs we’d thought they were. In fact, they’d won awards before we even stepped aboard, but they’d apparently been holding back until now. That night, it became clear they’d been teasing us all along, doling out the wishy-washy soups and boiled eggs just to see how we’d react.

In hindsight, I couldn’t blame them. If I were in their shoes, I’d have probably done the same to a group of British sailors who spent the entire trip moaning about chips and ketchup. Still, as the dining-in night wrapped up, I made a silent vow: never again would I turn down dessert without a full briefing. You never know what surprises might be hiding behind a name like “Omelette Vesuvius.”

Poem

‘Pass the Dutchy from the left hand side’

Meant give the wishy wash soup to the port side of the ship

We’d sing this song at low and high tide

In the three months spent on this hollandaise trip

A memorable time was had by all,

In the eighties it was something Jack called fun

Missing the boat, those knickers would fall

Whilst beating out ‘crabs’ in the mid-day sun!

A tomato, a rissole a burger some days

Picnic eggs, reined supreme

Life on the Zuidercruise, was no malaise

In a Baked Alaskan dream

Sign on all the Dutch footballing cream

Hope the Scousers might finally find some fatigue

For Arne just, only a memory, of Jurgen’s team

Going Dutch up the Premier League.